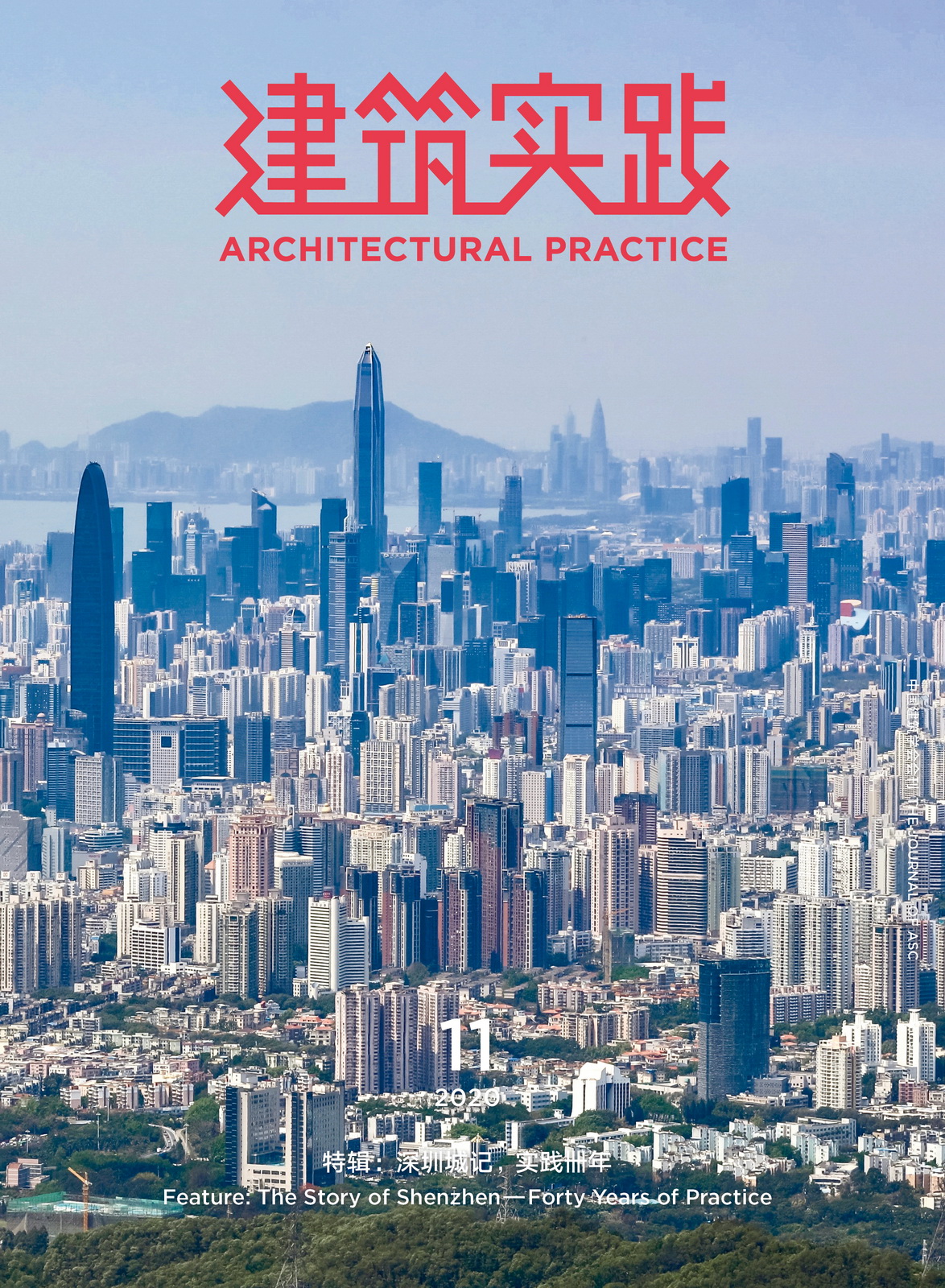

Journal Architectural Practice. Feature: The Story of Shenzhen – Forty Years of Practice 2020(11) 90-101

Please introduce the current organizational structure and staff composition of URBANUS, and make a periodic summary for its establishment and development in Shenzhen.

Throughout its history, URBANUS has now reached a relatively modest size of about 100 employees, including 70 in Shenzhen and 30 in Beijing. Actually, we are keep controlling the number of staff consciously: each of the three principal architects will be in charge of 20–30 people. On one hand, the size of the design team could be too small to finish some significant projects. On the other hand, if it’s too large, the principal’s input and control to the design can probably be weakened, which goes against our initial vision.

During the past two decades, the organizational structure of URBANUS has also undergone some changes and adjustments. In the first ten years, it was in the form of a workshop, with well-defined tasks and close cooperation. This promoted the overall brand image greatly, yet the individual characteristics of each work could still be strengthened further. In the next ten years, adjustments to this structure were made. We introduced a new system—the three principal architects have become independently responsible for their respective projects, which gives every principal architect a more independent operating space. Whether it is design thinking, research interest, or the project operation, the individuality can be more prominent. Nevertheless, what remains unchanged is the common concept of URBANUS, the continuous thinking of architectural and urban issues in the past two decades, and the value judgments of contemporary culture and urban development in URBANUS are always forward-looking and in consensus.

Co-existence with differences is not only an expansion of URBANUS’s concept, but also an exploration for organization and modes of operation. If a company wants to develop steadily for a long time, it must constantly reflect on itself, bring forth the new, and look for new possibilities.

What did you and your co-founders think when you came to Shenzhen? Under what circumstances and personal ideals did you found URBANUS in 1999?

The three of us have different backgrounds, personalities, hobbies and work styles, yet we were all born in the 1960s, and what we share in common is our prominent ideals and inter-generational characteristics, which rooted in the 1980s.

Known as the “Golden Decade”, the 1980s was the most idealistic and pure era of China’s reform and opening up, during which we received architectural education. In the 1990s, when commercialization and consumerism prevailed, we went abroad to study and work, receiving an optimistic and imaginative cultural atmosphere, together with rigorous and practical academic and professional training. In 1999, we witnessed the arrival of the new century in Times Square, New York, and had the idea that we should return to China to have a career.

Maybe we couldn’t form a clear understanding and judgment to the current historical process. Nevertheless, as witnesses, when we look back we can clearly find how times changed. This is exactly the charm of history.

How were the urban atmosphere and construction industry development in Shenzhen when URBANUS was founded?

Before we founded URBANUS in 1999, I had been to Shenzhen twice. The first time I visited Shenzhen was in 1988, when the city was under construction and I was fortunate to see the highlights of Shenzhen University’s development. When I came to Shenzhen again in 1995, the city had already undergone rapid development for 15 years. It was also the first time I realized that Shenzhen is a historical city and not “built in a day” after I “met” Dongmen Old Street.

For me, I had been slowly accumulating experience before the 1990s. Having lived in Beijing for 20–30 years, I have deep insights into Beijing, a city with a profound cultural tradition and undergoing a great transformation. When I came to New York—a crazy global metropolis—I’ve developed a new understanding to the essence of metropolitan life. After going through these two completely different urban lives, influenced by both Chinese traditional culture and contemporary culture, I was eager to find a place to experiment and fulfill what I thought out of conviction and idealism. For one design project, I revisited Shenzhen for the third time in 1999, I gradually found that this city might be the testing ground that I had been looking for.

Once you have gathered too many thoughts, ideas and methods, all your strength is ready to be applied, and then when you happen to be met with an opportunity, you will strive at any cost. At that time, we felt that Shenzhen was a suitable place for starting up a new business—it neither had too much prejudice, nor solid regional or cultural boundaries. The reason why Shenzhen attracts us is that it provides lots of opportunities. Designers, no matter local or overseas, experienced or young, can feel its openness and tolerance.

Shenzhen shows a special sense of contradiction and conflict, including in terms of planning and grass-roots growth, innovation and history, etc. Is this one of the sources of its vitality?

Many people believe that Shenzhen developed from a top-down power, and criticize that Shenzhen—although located in southern China—was planned as a “northern city” by some northerners. Indeed, if you come to the central area of Futian District, you will be shocked by the great scale, wide streets and magnificent monumentality, giving it a strong northern character. In contrast, Guangzhou is a very typical southern city. The complex and dense blocks, dense greenery, narrow streets, etc., all reflect the characteristics of a southern city.

But in fact, Shenzhen is neither like Beijing, Guangzhou, nor Hong Kong. It is a city sample of extreme artificialization. On one hand, you can feel the planning, order and efficiency everywhere—the building height in Futian Central District and the city skyline are carefully designed and strictly implemented, which is unique in the history of Chinese urban development. On the other hand, because Shenzhen is located in Guangdong, the geographic characteristic gives it a strong sense of marginality and distance in political, economic, and cultural aspects. The civil society in Guangdong is so powerful that sometimes they could even compete with the top-down planning order, power and capital.

In addition, the emergence of a stronger civil power in Shenzhen is also related to the concept of city managers. Although the system’s power is strong, it is relatively more pragmatic, with southern wisdom of flexibility. Faced with difficult problems, it’s not always necessary to use power to solve problems forcefully. Instead, it may temporarily put it aside or use market mechanisms, and then take a relatively secure method to “cross the river by feeling the stones” and to play it by ear. Why can many villages inside the city survive? The real experimentation behind this phenomenon is exactly the wisdom of Shenzhen.

Contradictions and conflicts between values such as experimental and practical, public welfare and utilitarian etc., always coexist at the same time through the development of Shenzhen. Therefore, as we see it today, the urban character of Shenzhen, whether appreciatively or critically speaking, has already shown in that era. The urban cultural genes derived from weakening ideology and advocating a pragmatic spirit since the 1980s still remain.

What are the most prominent characteristics of Shenzhen? How did they generate and change?

The vigor, innovation and creativity of Shenzhen began to appear at the turn of this century. In 2004–2005, the urbanization of Shenzhen entered another stage, undergoing a drastic transformation, and climaxed in 2010–2011. I think Shenzhen was in its best state during the first 10–15 years of URBANUS (about 1999–2014). Why? Because everyone was growing wildly.

As a small office, our power was very limited, but at that time, many people were willing to listen and make changes. Even from 2012 to 2016, in the trend of urban regeneration, we also initiated the preservation of Shenzhen Hubei Old Village with many professionals, among which include more than 100 people with architecture or urban planning backgrounds and personages from culture, art, and media communities. Actually, the fact that people are willing to participate in the protection of such an old village in the city, which has no direct connection with their daily lives, shows the common desire of people in Shenzhen to use innovative concepts and methods to solve problems and thus make the city better. At that time, city managers, architects, and entrepreneurs all had experienced a huge change, constantly growing and absorbing new ideas, knowledge, and concepts. Everyone is striving for a better goal. Today, either the vigor or the maze formed by challenges and problems along the way should be seen as a special character of a specific era. If a city finds its exact direction prematurely and has no possibility of any breakthrough—as if one person’s future has been determined long ago—this may be the time when it should start over.

Shenzhen is quite an interesting city. It is very civic. People often criticize their own city and look for changes. This is a driving force for urban development. Although the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was founded 40 years ago, it is still a young city and should avoid premature formation and finalization. Actually, the self-definition of a city takes a long time. London, New York, Tokyo, and Hong Kong have all gone through a long period of accumulation before they became what they should be. In terms of the current situation, each city has its own distinctive characteristics—the magnanimity and casualness of Beijing, and the sweetness and petit-bourgeois of Shanghai, both required centuries to form. If Shenzhen gives up some of its own characteristics prematurely or infuses other cities’ mature experience, it will be too hasty. The city should leave sufficient room for itself, and avert restricting its activities to a designated area.

Urban construction and the construction industry will be affected by policies and urban planning. In turn, the efforts of design institutes and offices or some large-scale events may also affect the formulation of policies. What do you think about the common development of URBANUS and Shenzhen?

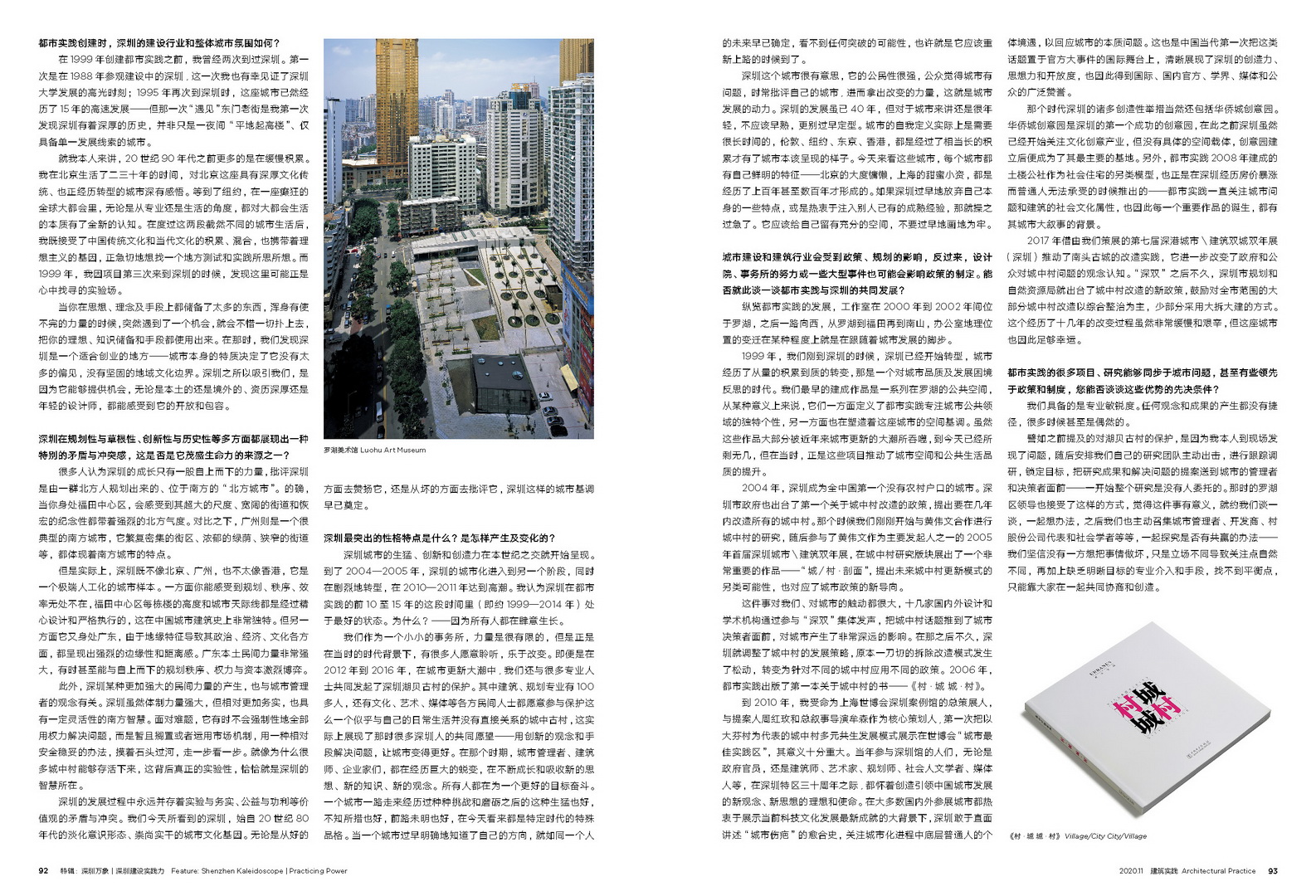

When looking at the development of URBANUS, our office was in Luohu District from 2000 to 2002, and then moved westward to Futian District and then to Nanshan District. To some extent, the change of office location is following the pace of urban development.

In 1999, when we just arrived to Shenzhen, this city had started to transform, from pursuing quantity to quality. That was an era of reflecting on urban quality and development challenges. Our earliest built works are a series of public spaces in Luohu District. In a sense, they define the unique personality of URBANUS and form the spatial tone of the city. Although these works were mostly demolished in the trend of urban regeneration and not much is left, they promoted the improvement of urban space and the quality of public life.

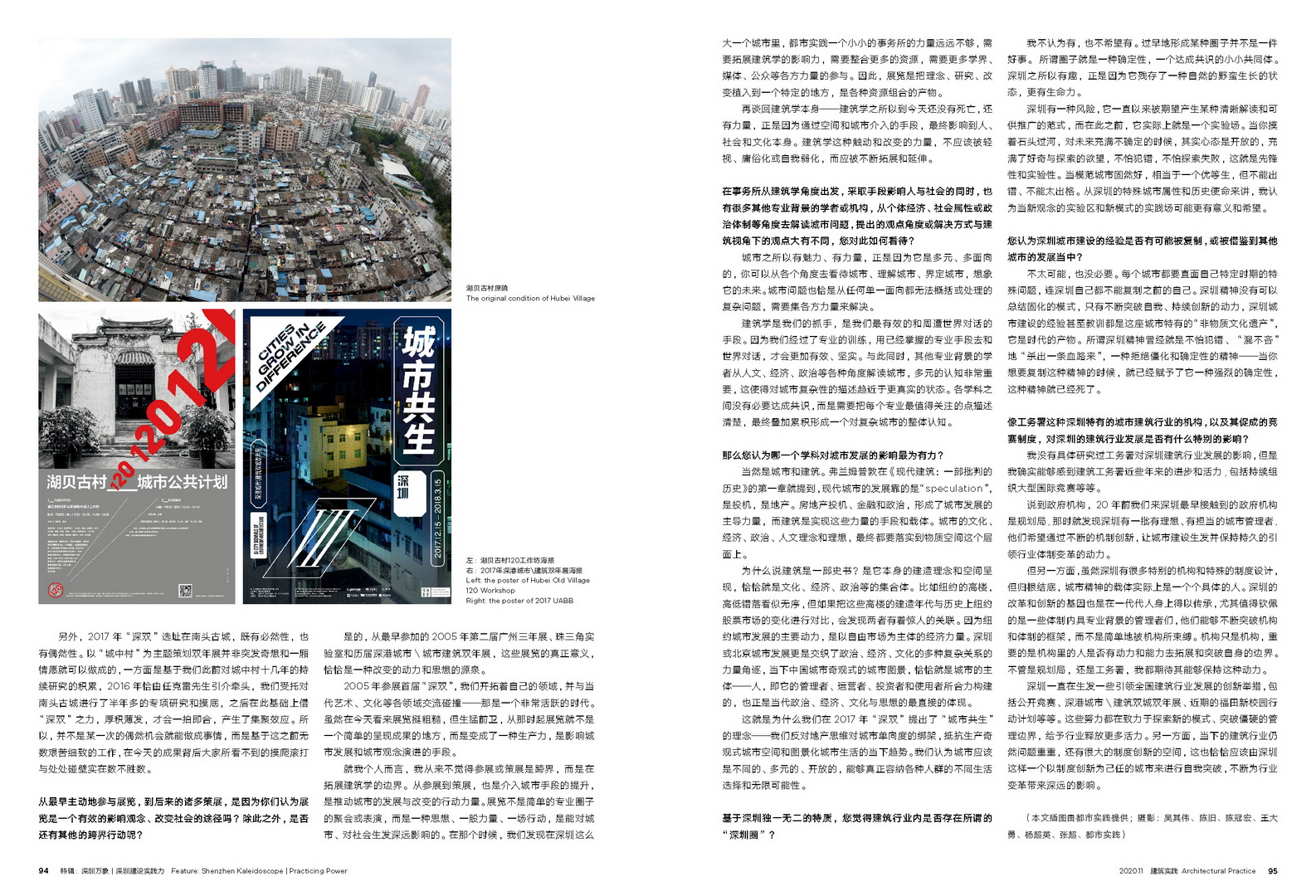

In 2004, Shenzhen became the first city in China without rural registration. Shenzhen Municipal Government also came up with the first policy on the transformation of urban villages, proposing to transform all villages within a few years. At that time, we had just started to cooperate with HUANG Weiwen on the research of urban villages, and then participated in the first Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture in 2005 in which HUANG Weiwen was one of the main campaigners. A very important work was exhibited in the research section on urban villages—the “City/Village Section”, which proposed alternative possibilities for the renewal mode of future urban villages, corresponding to the new orientation of urban policy.

This incident has a great impact on us and the city. More than a dozen domestic and foreign design and academic institutions have participated in Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture, putting forward the topic of urban villages to the governors, which had a profound impact on the city. Soon after that, Shenzhen adjusted its development strategy for urban villages. The original “one-size-fits-all” demolition and reconstruction model was loosened and changed to apply different policies for different urban villages. In 2006, URBANUS published the first book about urban villages—Village/City · City/Village.

In 2010, I was appointed as the Chief Curator of the Shanghai Expo—Shenzhen Case Pavilion, with the organizer ZHOU Hongmei and Chief Director MU Sen as the core planners, and for the first time we presented the multi-symbiosis development model of urban villages represented by Dafen Village in the “Urban Best Practice Area” (UBPA) of the World Expo. People who participated in the Shenzhen Case Pavilion then, including government officials, architects, artists, planners, social and humanities scholars, media professionals, etc., on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, all had new ideas and concepts that lead the development of Chinese cities. Under the background that most of the participating cities at home and abroad were keen to show the latest achievements in current technological and cultural development, Shenzhen had the courage to talk about the healing history of “urban scars” and paid attention to the individual situation of ordinary people at the bottom of the urbanization process in response to the city’s essential question. This is also the first time that contemporary China has put such topics on the international stage of official events, clearly showing Shenzhen’s creativity, intellectuality and openness, and it has also been widely praised by international and domestic officials, academia, media and the public.

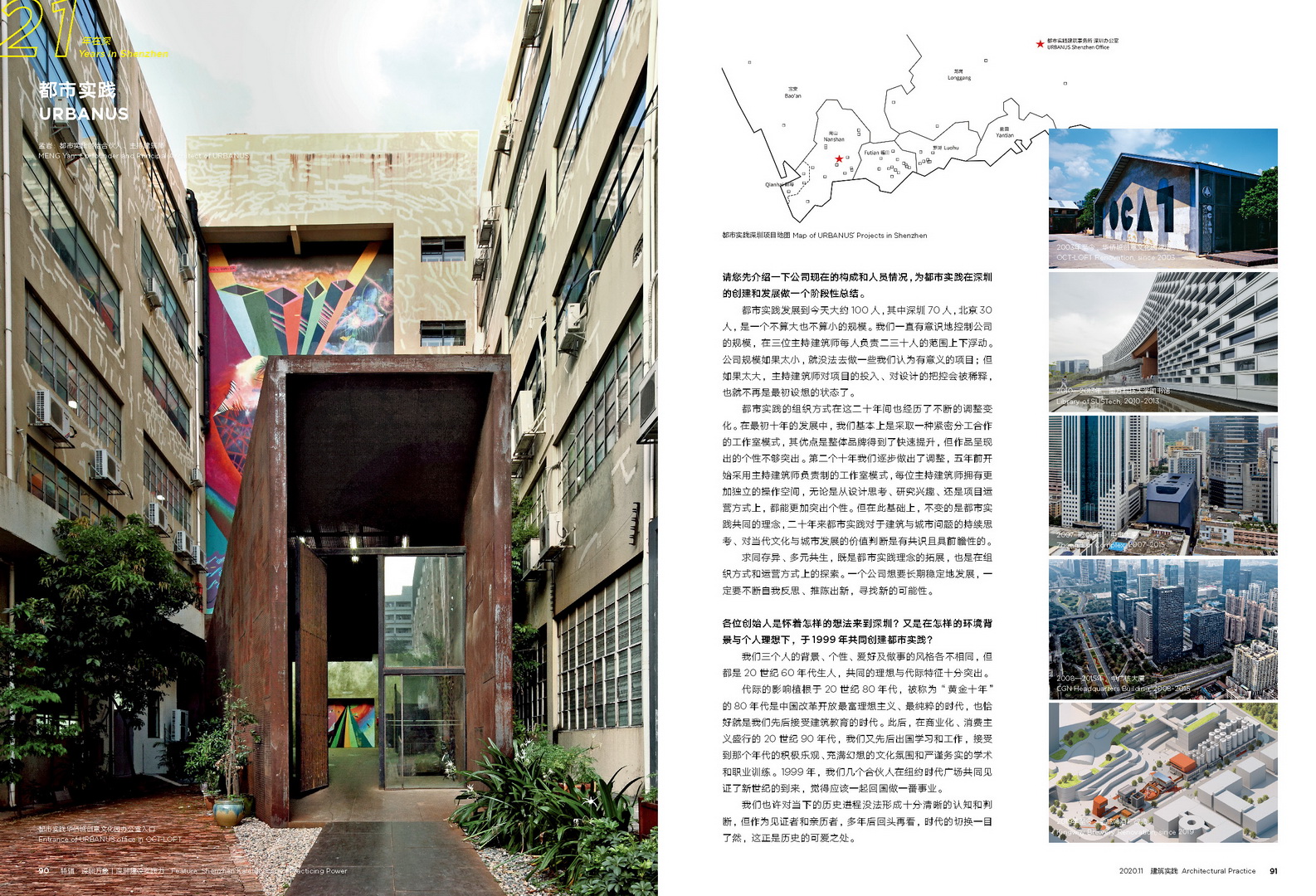

OCT-LOFT is a typical case among the creative moves in Shenzhen at that time. OCT-LOFT is the first successful creative park in Shenzhen. Before that Shenzhen had also begun to pay attention to the cultural and creative industries, but there is no specific spatial entity. Once established, OCT-LOFT has become its main base. In addition, the Tulou Collective Housing built in 2008, as an alternative model of social housing, was launched at a time when Shenzhen experienced skyrocketing housing prices that ordinary people could not afford. URBANUS has always paid attention to urban issues and to the social and cultural attributes of buildings. Every important work is therefore rooted in the background of urban narrative.

In 2017, the 7th SZ-HK Bi-city Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) curated by URBANUS promoted the transformation of Nantou Old Town, which further changed the government and the public’s perception of urban villages. Soon after the Biennale, the Shenzhen Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources issued a new policy for the renewal of urban villages, encouraging most of the city-wide urban villages to focus on comprehensive improvement, while a few of the villages adapted the methods of large-scale demolition and reconstruction. Although this process of change over the course of more than ten years is very slow and difficult, the city is lucky for it.

Many projects and research of URBANUS respond to or echo urban issues, and some are even ahead of policies and regulations. Can you talk about how you have gained these advantages?

What we have is professional sensitivity. There are no shortcuts to the production of any ideas and outcomes, and in many cases, it is even accidental.

For example, the protection of the Hubei Old Village mentioned earlier was because I discovered the problem once I arrived at the site, and then arranged our own research team to carry out follow-up investigations, lock targets, and submit research results and problem-solving proposals to the governors—the entire research was voluntary at the beginning. At that time, the leaders of Luohu District also accepted this approach. They felt that this was meaningful, so they invited us to have a conversation and think of ways together. After that, we also took measures to gather city managers, developers, representatives of the village stock company, and social scholars, trying to explore whether there is a win-win solution—we firmly believed that everyone wants to get things done properly, but different positions lead to different concerns. In addition, there was lack of professional intervention and means for clear goals, and there was no balance. We can only rely on everyone to negotiate and create together.

The fact that the 2017 UABB selected Nantou Old Town as the site has necessity and contingency. Curating the Biennale with the theme of “Urban Villages” is not from ones wishful thinking. On one hand, it is based on our previous accumulation of more than ten years of continuous research on urban villages. In 2016, introduced and led by Mr. REN Kelei, we were commissioned to conduct special research and investigation on the Nantou Old Town for more than half a year, and then on this basis, we took advantage of the Biennale and produced an agglomerative effect. Therefore, it is not just an accidental opportunity that things can be done, but because of the previous countless hard and meticulous work. Behind today’s achievements, there were innumerable difficulties and obstacles.

From participating in exhibitions to curating, do you think the exhibition is an effective way to influence ideas and change society? Apart from this, are there other cross-border actions?

Yes, at the beginning we have participated in the second Guangzhou Triennial in 2005, the Delta Laboratory (D-Lab), then all the previous UABB; the true meanings of these exhibitions are a source of motivation and ideas for change.

In 2005, when getting involved in the first UABB, we were expanding our own fields, and interacting with contemporary art, culture and other fields—it was a very active era. Although the exhibition looks rough today, it is avant-garde. Since then, the exhibition has not been a simple place to present results, but has become a kind of productivity, a measure to influence urban development and the evolution of urban concepts.

As far as I am concerned, I don’t think of exhibiting or curating as “crossing boundaries”, but rather as an expansion of architecture. From exhibiting to curating, it is also the improvement of the means of intervening in the city, and a force of action to promote the development and change of the city. Exhibition is not a simple gathering or performance of professional circles, but an idea, a force, and an action that can have a profound impact on the city and society. At that time, we found that in such a big city like Shenzhen, the power of URBANUS is far from enough. It is necessary to expand the influence of architecture, integrate more resources, and gather more academic circles, the media, the public and other parties. Therefore, the exhibition is to implant ideas, research, and changes into a specific place; it is the product of a combination of various resources.

Back to architecture in and of itself, the reason why architecture as a discipline has not died till now and still has power is that it affects people, society and culture itself through space and urban intervention. The power of architecture to trigger and make changes should not be underestimated, vulgarized, or self-weakened, but should continue to expand and extend its boundaries.

Design studios, from a perspective of architecture, will take measures to have effects on society and people. Also, there are many scholars or institutions with other professional backgrounds interpreting urban issues economically, socially or politically and they may come up with opinions or solutions quite different from architects. How do you feel about this?

The reason why a city is attractive and powerful is the diversity and versatility. People can look at the city from all perspectives, understand it, define it, and imagine its future. The urban problem is also a complex problem that cannot be summarized or dealt with in any single aspect. It needs to be solved by all parties.

Architecture is our most effective means to speak with the world around us. Because we have undergone professional training and use professional means, it will be more effective and solid. At the same time, scholars with other professional backgrounds interpret cities from various perspectives such as humanities, economics, and politics, implying that multiple cognitions are very important, which makes the description of the complexity of cities approach a more realistic situation. There is no need to reach a consensus among various disciplines, but we should clearly describe the most noteworthy points of each discipline, and finally superimpose and accumulate to form an overall understanding of complex cities.

Which discipline do you think has the most powerful influence on urban development?

Urban planning and architecture, of course. Kenneth Frampton mentioned in the first chapter of his book Modern Architecture: A Critical History that the development of modern cities relied on “speculation”, namely that of real estate. Real estate speculation, finance, and politics have formed the dominant forces in urban development, and architecture is the means and carrier to realize these forces. The culture, economy, politics, and humanistic concepts and ideals of a city must ultimately be implemented on the level of physical space.

Architecture is like a history book—its own construction concept and spatial presentation are exactly a collection of culture, economy, and politics. For example, the high-rise buildings in New York seem to be disorderly, but if you compare the construction years of these high-rise buildings with the changes in the New York stock market in history, you will find that the two are surprisingly related. Because the main driving force of New York’s urban development is economic power with the free market as the main body. The urban development of Shenzhen or Beijing is a competition of forces that are intertwined with multiple complex relationships of politics, economy, and culture. The current Chinese urban landscape is precisely constructed by its managers, operators, investors and users, directly manifesting contemporary politics, economy, culture, and ideas.

That is why we proposed “Cities, Grow in Difference” in the 2017 UABB. We oppose the kidnapping of cities by real estate thinking and appeal for resisting the current trend of producing marvelous urban spaces and visualized urban life. We believe that cities should be different, diverse, and open, truly accommodating the different life choices and infinite possibilities of various people.

Considering the special characteristics of Shenzhen, do you agree that there is a so-called “Shenzhen Circle” in the architecture industry?

I don’t think so. It is not a good thing to form a certain circle prematurely. The so-called circle is a kind of certainty, a small community that reaches a consensus. The reason why Shenzhen is interesting is precisely that it has a natural state of savage growth and more vitality.

There is a risk in Shenzhen. As an experimental ground of the reform and opening-up, it has always been expected to produce a clear interpretation and a paradigm that can be promoted. When you cross the river by feeling the stones and are full of uncertainty about the future, you are actually open-minded, full of curiosity and desire to explore, not afraid of mistakes and failures. This is pioneering and experimental. Being a model city is good, but you can never go wrong or out of line. In terms of Shenzhen’s special urban attributes and historical mission, I think it may be more meaningful and hopeful to be an experimental area for new concepts and a practice field for new models and patterns.

To what extent can the experience of the urban construction of Shenzhen be copied or used for reference in the development of other cities?

It seems impossible, and unnecessary. Each city has to face directly its specific problems at a particular period. Even Shenzhen itself can’t copy its previous experience. There is no pattern that can be summarized and solidified for the Shenzhen spirit, only the drive to continuously break through and innovate. The experiences and lessons of Shenzhen’s urban construction are the unique “intangible cultural heritage” of this city, which is the product of the times. The so-called “Shenzhen spirit” was a spirit that rejected rigidity and certainty—whenever you want to copy this spirit, you have already given it a strong certainty, and then the spirit is dead.

Institutions like the Bureau of Public Works of Shenzhen Municipality, which only exists in Shenzhen, have brought about the design competition system. Does it have any special impact on the development of Shenzhen’s construction industry?

I have not specifically studied the impact of the Bureau of Public Works on the development of the construction industry in Shenzhen, but I do feel the progress and vitality of the Bureau of Public Works in recent years, including organizing various large-scale international competitions.

When it comes to government agencies, the first one we came into contact with was the Shenzhen Planning Bureau when we came to Shenzhen 20 years ago. At that time, we discovered that there were a group of city managers with ideals and responsibilities in Shenzhen. They hoped to promote a continuous mechanism for innovation, making urban construction produce and maintain a lasting driving force to lead a systematic reform of the industry.

On the other hand, while there are many special institutions and designed systems in Shenzhen, in the end, the urban spirit is carried by each specific individual. The genes of the reform and innovation in Shenzhen have also been passed on from generation to generation. It is especially admirable that some managers with professional backgrounds in the system can continuously break through the framework of institution and system, rather than simply being constrained by them. What matters is whether the people in the organization have the motivation and ability to expand and break through their own boundaries. Whether it is the Planning Bureau or the Bureau of Public Works, I look forward to their maintaining this momentum.

Shenzhen has been taking innovative measures, such as open competitions, UABB, and the recent Futian New School Initiative, leading the development of the nation-wide construction industry. These efforts are dedicated to explore new models to break through rigid management boundaries and give the industry more vitality. On the other hand, the current situation of the construction industry is still full of problems, and there are still a lot of possibilities for institutional innovation. This is precisely where a city like Shenzhen takes institutional innovation as its mission in order to make self-breakthroughs and to continue bringing profound influence towards transforming the industry.