The article is written by LUO Yiqian, researcher of URBANUS, referencing URBANUS studies and practices of Nantou Old Town since 2016.

In 2004, Shenzhen became the first city in China with 100% urbanization, officially free of rural administrative divisions and the rural social system.1 Since the reform and opening up, the urbanization process of Shenzhen, firstly, has been led by the government and state-owned enterprises, followed by extensive implementation carried out by real-estate developers that guided by urban planning. On the other hand, in parallel with the top-down approach of development, plant and housing built on rural collective land as well as labor force from rural areas have also greatly contributed to the rapid urbanization of Shenzhen. Driven by the left-over dual system of land tenure and the surging demand for marketization, self-led informal construction activities developed today’s urban villages.

What also happened in 2004 was that the Shenzhen government promulgated the renovation policy on urban villages, officially starting the work of transforming urban villages.2 Back then, urban villages as a phenomenon of informality were regarded as a flaw in the “perfect urbanization” and for a time referred to as the “urban cancers”. In 2012, the area of existing land use exceeded that of new land use in Shenzhen for the first time in history, which marked the turning point of land development models.3 In the recent two years, there has been a continuous call for re-urbanization.4 The urban villages, which were not built under planning nor transformed as policies require but are situated in the city center, have inevitably become new frontiers of the game.

The tension between urban villages and the city at large has been becoming more and more pronounced. From a temporal perspective, the former and the latter are both narratives of Shenzhen’s history of urban development, respectively, on an individual level and a macro level. In fact, the two are inseparable, as Shenzhen cannot move toward a future discarding its own history. The regeneration model for urban villages, to a great extent, indicates the future pathway of the city’s urban development.

1. Mainstream Regeneration Model for Urban Villages

In the past two decades, hundreds of urban villages in Shenzhen have been in both ecstasy and anxiety caused by the upcoming demolition.5 Large urban villages, such as Caiwuwei, Gangsha and Dachong, were thoroughly demolished and rebuilt. Led by the government and constructed by developers, high-rise office buildings, shopping malls, and high floor-area-ratio residential buildings replaced “handshake buildings”, once and on a large scale, thus creating an image of the modern city. The regeneration of these villages has brought profits to developers and compensation package to villagers.

Nevertheless, how many KK100s or MIXCs Shenzhen is needing? Who is paying for the huge cost of compensation for urban village demolition?

As an aftermath of the regeneration model by complete replacement, the original lifestyle in urban villages disappeared instantly and thoroughly, as if they never existed. Losing their affordable living space, millions of tenants had to move to other surviving urban villages or leave the city for good. As these communities move away, the city’s operational cost rises, its memory fades, and the urban identity becomes hard to accumulate. This regeneration model comes at the cost of the distinctive feature, history and one or multiple future possibilities of Shenzhen.

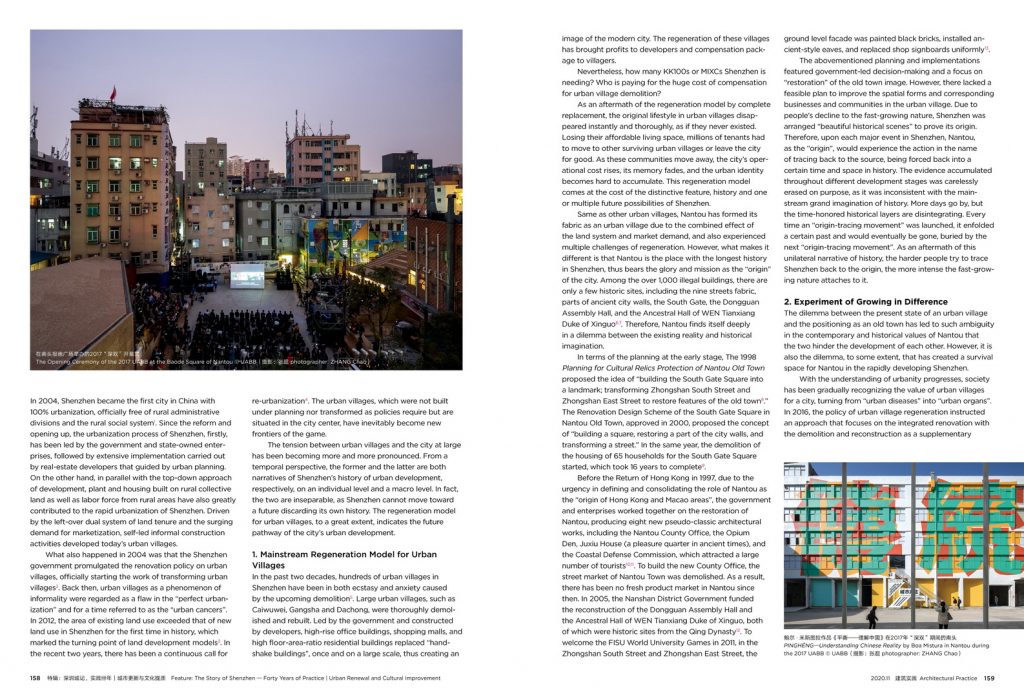

Same as other urban villages, Nantou has formed its fabric as an urban village due to the combined effect of the land system and market demand, and also experienced multiple challenges of regeneration. However, what makes it different is that Nantou is the place with the longest history in Shenzhen, thus bears the glory and mission as the “origin” of the city. Among the over 1,000 illegal buildings, there are only a few historic sites, including the nine streets fabric, parts of ancient city walls, the South Gate, the Dongguan Assembly Hall, and the Ancestral Hall of WEN Tianxiang Duke of Xinguo.6,7 Therefore, Nantou finds itself deeply in a dilemma between the existing reality and historical imagination.

Southern Gate of Nantou Old Town before the 2017 UABB © URBANUS

In terms of the planning at the early stage, The 1998 Planning for Cultural Relics Protection of Nantou Old Town proposed the idea of “building the South Gate Square into a landmark; transforming Zhongshan South Street and Zhongshan East Street to restore features of the old town.”8 The Renovation Design Scheme of the South Gate Square in Nantou Old Town, approved in 2000, proposed the concept of “building a square, restoring a part of the city walls, and transforming a street.” In the same year, the demolition of the housing of 65 households for the South Gate Square started, which took 16 years to complete.9

Zhongshan South Street in Nantou before the 2017 UABB © URBANUS

Before the Return of Hong Kong in 1997, due to the urgency in defining and consolidating the role of Nantou as the “origin of Hong Kong and Macao areas”, the government and enterprises worked together on the restoration of Nantou, producing eight new pseudo-classic architectural works, including the Nantou County Office, the Opium Den, Juxiu House (a pleasure quarter in ancient times), and the Coastal Defense Commission, which attracted a large number of tourists.10,11 To build the new County Office, the street market of Nantou Town was demolished. As a result, there has been no fresh product market in Nantou since then. In 2005, the Nanshan District Government funded the reconstruction of the Dongguan Assembly Hall and the Ancestral Hall of WEN Tianxiang Duke of Xinguo, both of which were historic sites from the Qing Dynasty.12 To welcome the FISU World University Games in 2011, in the Zhongshan South Street and Zhongshan East Street, the ground level facade was painted black bricks, installed ancient-style eaves, and replaced shop signboards uniformly.13

The abovementioned planning and implementations featured government-led decision-making and a focus on “restoration” of the old town image. However, there lacked a feasible plan to improve the spatial forms and corresponding businesses and communities in the urban village. Due to people’s decline to the fast-growing nature, Shenzhen was arranged “beautiful historical scenes” to prove its origin. Therefore, upon each major event in Shenzhen, Nantou, as the “origin”, would experience the action in the name of tracing back to the source, being forced back into a certain time and space in history. The evidence accumulated throughout different development stages was carelessly erased on purpose, as it was inconsistent with the mainstream grand imagination of history. More days go by, but the time-honored historical layers are disintegrating. Every time an “origin-tracing movement” was launched, it enfolded a certain past and would eventually be gone, buried by the next “origin-tracing movement”. As an aftermath of this unilateral narrative of history, the harder people try to trace Shenzhen back to the origin, the more intense the fast-growing nature attaches to it.

2. Experiment of Growing in Difference

The dilemma between the present state of an urban village and the positioning as an old town has led to such ambiguity in the contemporary and historical values of Nantou that the two hinder the development of each other. However, it is also the dilemma, to some extent, that has created a survival space for Nantou in the rapidly developing Shenzhen.

With the understanding of urbanity progresses, society has been gradually recognizing the value of urban villages for a city, turning from “urban diseases” into “urban organs”. In 2016, the policy of urban village regeneration instructed an approach that focuses on the integrated renovation with the demolition and reconstruction as a supplementary method.14 On the practical level, powerful entities still control, unilaterally, the decision-making and implementation of the integrated renovation of urban villages. In 2017, Vanke launched its “Ten-thousand Villages Plan”, a project targeting the transformation of urban villages, to source over 100,000 units and rent them out after standardized renovation as brand long-term apartments.15

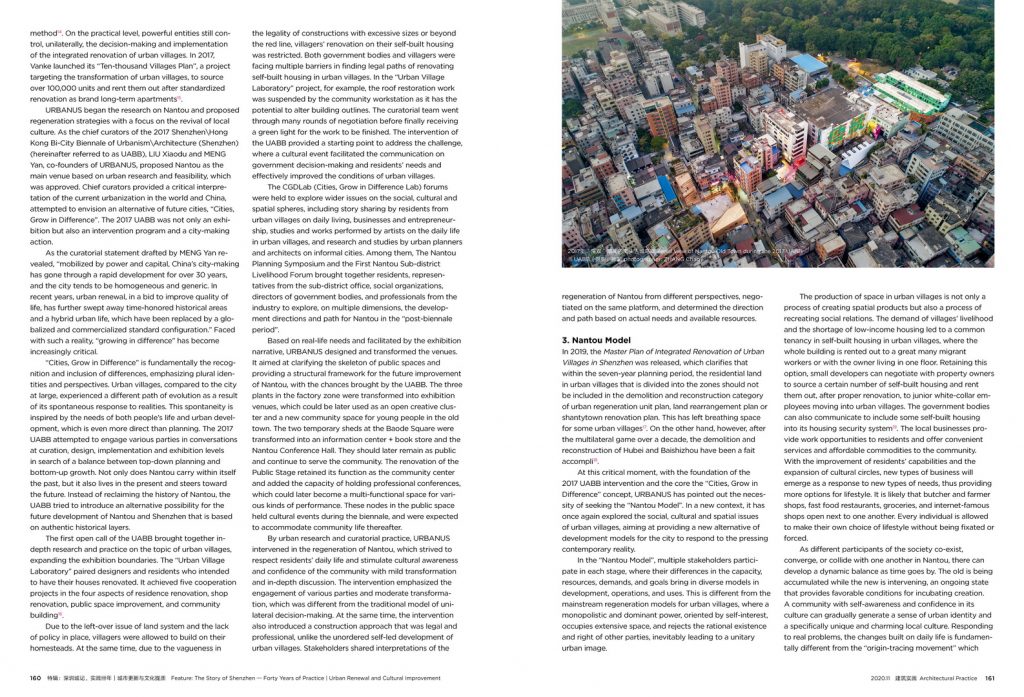

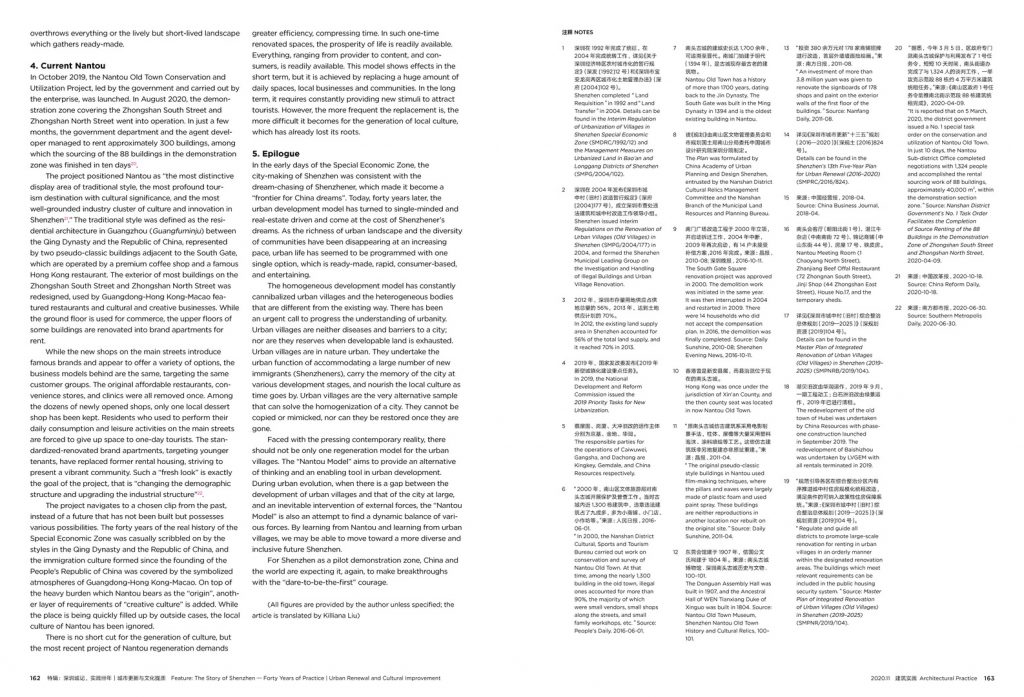

URBANUS began the research on Nantou and proposed regeneration strategies with a focus on the revival of local culture. As the chief curators of the 2017 Shenzhen\Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (Shenzhen) (hereinafter referred to as UABB), LIU Xiaodu and MENG Yan, co-founders of URBANUS, proposed Nantou as the main venue based on urban research and feasibility, which was approved. Chief curators provided a critical interpretation of the current urbanization in the world and China, attempted to envision an alternative of future cities, “Cities, Grow in Difference”. The 2017 UABB was not only an exhibition but also an intervention program and a city-making action.

Nantou before the 2017 UABB © UABB

As the curatorial statement drafted by MENG Yan revealed, “mobilized by power and capital, China’s city-making has gone through a rapid development for over 30 years, and the city tends to be homogeneous and generic. In recent years, urban renewal, in a bid to improve quality of life, has further swept away time-honored historical areas and a hybrid urban life, which have been replaced by a globalized and commercialized standard configuration.” Faced with such a reality, “growing in difference” has become increasingly critical.

“Cities, Grow in Difference” is fundamentally the recognition and inclusion of differences, emphasizing plural identities and perspectives. Urban villages, compared to the city at large, experienced a different path of evolution as a result of its spontaneous response to realities. This spontaneity is inspired by the needs of both people’s life and urban development, which is even more direct than planning. The 2017 UABB attempted to engage various parties in conversations at curation, design, implementation and exhibition levels in search of a balance between top-down planning and bottom-up growth. Not only does Nantou carry within itself the past, but it also lives in the present and steers toward the future. Instead of reclaiming the history of Nantou, the UABB tried to introduce an alternative possibility for the future development of Nantou and Shenzhen that is based on authentic historical layers.

The first open call of the UABB brought together in-depth research and practice on the topic of urban villages, expanding the exhibition boundaries. The “Urban Village Laboratory” paired designers and residents who intended to have their houses renovated. It achieved five cooperation projects in the four aspects of residence renovation, shop renovation, public space improvement, and community building.16

PINGHÉNGⅩUnderstanding Chinese Reality by Boa Mistura in Nantou during the 2017 UABB © UABB (photographer: ZHANG Chao)

PINGHÉNGⅩUnderstanding Chinese Reality by Boa Mistura in Nantou during the 2017 UABB © UABB (photographer: ZHANG Chao)

Due to the left-over issue of land system and the lack of policy in place, villagers were allowed to build on their homesteads. At the same time, due to the vagueness in the legality of constructions with excessive sizes or beyond the red line, villagers’ renovation on their self-built housing was restricted. Both government bodies and villagers were facing multiple barriers in finding legal paths of renovating self-built housing in urban villages. In the “Urban Village Laboratory” project, for example, the roof restoration work was suspended by the community workstation as it has the potential to alter building outlines. The curatorial team went through many rounds of negotiation before finally receiving a green light for the work to be finished. The intervention of the UABB provided a starting point to address the challenge, where a cultural event facilitated the communication on government decision-making and residents’ needs and effectively improved the conditions of urban villages.

The CGDLab (Cities, Grow in Difference Lab) forums were held to explore wider issues on the social, cultural and spatial spheres, including story sharing by residents from urban villages on daily living, businesses and entrepreneurship, studies and works performed by artists on the daily life in urban villages, and research and studies by urban planners and architects on informal cities. Among them, The Nantou Planning Symposium and the First Nantou Sub-district Livelihood Forum brought together residents, representatives from the sub-district office, social organizations, directors of government bodies, and professionals from the industry to explore, on multiple dimensions, the development directions and path for Nantou in the “post-biennale period”.

Based on real-life needs and facilitated by the exhibition narrative, URBANUS designed and transformed the venues. It aimed at clarifying the skeleton of public spaces and providing a structural framework for the future improvement of Nantou, with the chances brought by the UABB. The three plants in the factory zone were transformed into exhibition venues, which could be later used as an open creative cluster and a new community space for young people in the old town. The two temporary sheds at the Baode Square were transformed into an information center + book store and the Nantou Conference Hall. They should later remain as public and continue to serve the community. The renovation of the Public Stage retained its function as the community center and added the capacity of holding professional conferences, which could later become a multi-functional space for various kinds of performance. These nodes in the public space held cultural events during the biennale, and were expected to accommodate community life thereafter.

The Opening Ceremony of the 2017 UABB at the Baode Square of Nantou © UABB (photographer: ZHANG Chao)

By urban research and curatorial practice, URBANUS intervened in the regeneration of Nantou, which strived to respect residents’ daily life and stimulate cultural awareness and confidence of the community with mild transformation and in-depth discussion. The intervention emphasized the engagement of various parties and moderate transformation, which was different from the traditional model of unilateral decision-making. At the same time, the intervention also introduced a construction approach that was legal and professional, unlike the unordered self-led development of urban villages. Stakeholders shared interpretations of the regeneration of Nantou from different perspectives, negotiated on the same platform, and determined the direction and path based on actual needs and available resources.

3. Nantou Model

In 2019, the Master Plan of Integrated Renovation of Urban Villages in Shenzhen was released, which clarifies that within the seven-year planning period, the residential land in urban villages that is divided into the zones should not be included in the demolition and reconstruction category of urban regeneration unit plan, land rearrangement plan or shantytown renovation plan. This has left breathing space for some urban villages.17 On the other hand, however, after the multilateral game over a decade, the demolition and reconstruction of Hubei and Baishizhou have been a fait accompli.18

At this critical moment, with the foundation of the 2017 UABB intervention and the core the “Cities, Grow in Difference” concept, URBANUS has pointed out the necessity of seeking the “Nantou Model”. In a new context, it has once again explored the social, cultural and spatial issues of urban villages, aiming at providing a new alternative of development models for the city to respond to the pressing contemporary reality.

In the “Nantou Model”, multiple stakeholders participate in each stage, where their differences in the capacity, resources, demands, and goals bring in diverse models in development, operations, and uses. This is different from the mainstream regeneration models for urban villages, where a monopolistic and dominant power, oriented by self-interest, occupies extensive space, and rejects the rational existence and right of other parties, inevitably leading to a unitary urban image.

The production of space in urban villages is not only a process of creating spatial products but also a process of recreating social relations. The demand of villages’ livelihood and the shortage of low-income housing led to a common tenancy in self-built housing in urban villages, where the whole building is rented out to a great many migrant workers or with the owner living in one floor. Retaining this option, small developers can negotiate with property owners to source a certain number of self-built housing and rent them out, after proper renovation, to junior white-collar employees moving into urban villages. The government bodies can also communicate to include some self-built housing into its housing security system.19 The local businesses provide work opportunities to residents and offer convenient services and affordable commodities to the community. With the improvement of residents’ capabilities and the expansion of cultural circles, new types of business will emerge as a response to new types of needs, thus providing more options for lifestyle. It is likely that butcher and farmer shops, fast food restaurants, groceries, and internet-famous shops open next to one another. Every individual is allowed to make their own choice of lifestyle without being fixated or forced.

As different participants of the society co-exist, converge, or collide with one another in Nantou, there can develop a dynamic balance as time goes by. The old is being accumulated while the new is intervening, an ongoing state that provides favorable conditions for incubating creation. A community with self-awareness and confidence in its culture can gradually generate a sense of urban identity and a specifically unique and charming local culture. Responding to real problems, the changes built on daily life is fundamentally different from the “origin-tracing movement” which overthrows everything or the lively but short-lived landscape which gathers ready-made.

Aerial view of Nantou Old Town during the 2017 UABB (photographer: ZHANG Chao)

4. Current Nantou

In October 2019, the Nantou Old Town Conservation and Utilization Project, led by the government and carried out by the enterprise, was launched. In August 2020, the demonstration zone covering the Zhongshan South Street and Zhongshan North Street went into operation. In just a few months, the government department and the agent developer managed to rent approximately 300 buildings, among which the sourcing of the 88 buildings in the demonstration zone was finished in ten days.20

The project positioned Nantou as “the most distinctive display area of traditional style, the most profound tourism destination with cultural significance, and the most well-grounded industry cluster of culture and innovation in Shenzhen.”21 The traditional style was defined as the residential architecture in Guangzhou (Guangfuminju) between the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, represented by two pseudo-classic buildings adjacent to the South Gate, which are operated by a premium coffee shop and a famous Hong Kong restaurant. The exterior of most buildings on the Zhongshan South Street and Zhongshan North Street was redesigned, used by Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao featured restaurants and cultural and creative businesses. While the ground floor is used for commerce, the upper floors of some buildings are renovated into brand apartments for rent.

While the new shops on the main streets introduce famous brands and appear to offer a variety of options, the business models behind are the same, targeting the same customer groups. The original affordable restaurants, convenience stores, and clinics were all removed once. Among the dozens of newly opened shops, only one local dessert shop has been kept. Residents who used to perform their daily consumption and leisure activities on the main streets are forced to give up space to one-day tourists. The standardized-renovated brand apartments, targeting younger tenants, have replaced former rental housing, striving to present a vibrant community. Such a “fresh look” is exactly the goal of the project, that is “changing the demographic structure and upgrading the industrial structure”.22

The project navigates to a chosen clip from the past, instead of a future that has not been built but possesses various possibilities. The forty years of the real history of the Special Economic Zone was casually scribbled on by the styles in the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, and the immigration culture formed since the founding of the People’s Republic of China was covered by the symbolized atmospheres of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao. On top of the heavy burden which Nantou bears as the “origin”, another layer of requirements of “creative culture” is added. While the place is being quickly filled up by outside cases, the local culture of Nantou has been ignored.

There is no short cut for the generation of culture, but the most recent project of Nantou regeneration demands greater efficiency, compressing time. In such one-time renovated spaces, the prosperity of life is readily available. Everything, ranging from provider to content, and consumers, is readily available. This model shows effects in the short term, but it is achieved by replacing a huge amount of daily spaces, local businesses and communities. In the long term, it requires constantly providing new stimuli to attract tourists. However, the more frequent the replacement is, the more difficult it becomes for the generation of local culture, which has already lost its roots.

5. Epilogue

In the early days of the Special Economic Zone, the city-making of Shenzhen was consistent with the dream-chasing of Shenzhener, which made it become a “frontier for China dreams”. Today, forty years later, the urban development model has turned to single-minded and real-estate driven and come at the cost of Shenzhener’s dreams. As the richness of urban landscape and the diversity of communities have been disappearing at an increasing pace, urban life has seemed to be programmed with one single option, which is ready-made, rapid, consumer-based, and entertaining.

The homogeneous development model has constantly cannibalized urban villages and the heterogeneous bodies that are different from the existing way. There has been an urgent call to progress the understanding of urbanity. Urban villages are neither diseases and barriers to a city; nor are they reserves when developable land is exhausted. Urban villages are in nature urban. They undertake the urban function of accommodating a large number of new immigrants (Shenzheners), carry the memory of the city at various development stages, and nourish the local culture as time goes by. Urban villages are the very alternative sample that can solve the homogenization of a city. They cannot be copied or mimicked, nor can they be restored once they are gone.

Faced with the pressing contemporary reality, there should not be only one regeneration model for the urban villages. The “Nantou Model” aims to provide an alternative of thinking and an enabling tool in urban development. During urban evolution, when there is a gap between the development of urban villages and that of the city at large, and an inevitable intervention of external forces, the “Nantou Model” is also an attempt to find a dynamic balance of various forces. By learning from Nantou and learning from urban villages, we may be able to move toward a more diverse and inclusive future Shenzhen.

For Shenzhen as a pilot demonstration zone, China and the world are expecting it, again, to make breakthroughs with the “dare-to-be-the-first” courage.

(All figures are provided by the author unless specified; the article is translated by Killiana Liu)

NOTES

1 Shenzhen completed“Land Requisition” in 1992 and “Land Transfer” in 2004. Details can be found in the Interim Regulation of Urbanization of Villages in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SMDRC/1992/12) and the Management Measures on Urbanized Land in Bao’an and Longgang Districts of Shenzhen (SMPG/2004/102).

2 Shenzhen issued Interim Regulations on the Renovation of Urban Villages (Old Villages) in Shenzhen (SMPG/2004/177) in 2004, and formed the Shenzhen Municipal Leading Group on the Investigation and Handling of Illegal Buildings and Urban Village Renovation.

3 In 2012, the existing land supply area in Shenzhen accounted for 56% of the total land supply, and it reached 70% in 2013.

4 In 2019, the National Development and Reform Commission issued the 2019 Priority Tasks for New Urbanization.

5 The responsible parties for the operations of Caiwuwei, Gangsha, and Dachong are Kingkey, Gemdale, and China Resources respectively.

6 “In 2000, the Nanshan District Cultural, Sports and Tourism Bureau carried out work on conservation and survey of Nantou Old Town. At that time, among the nearly 1,300 building in the old town, illegal ones accounted for more than 90%, the majority of which were small vendors, small shops along the streets, and small family workshops, etc.” Source: People’s Daily. 2016-06-01.

7 Nantou Old Town has a history of more than 1700 years, dating back to the Jin Dynasty. The South Gate was built in the Ming Dynasty in 1394 and is the oldest existing building in Nantou.

8 The Plan was formulated by China Academy of Urban Planning and Design Shenzhen, entrusted by the Nanshan District Cultural Relics Management Committee and the Nanshan Branch of the Municipal Land Resources and Planning Bureau.

9 The South Gate Square renovation project was approved in 2000. The demolition work was initiated in the same year. It was then interrupted in 2004 and restarted in 2009. There were 14 households who did not accept the compensation plan. In 2016, the demolition was finally completed. Source: Daily Sunshine, 2010-08; Shenzhen Evening News, 2016-10-11.

10 Hong Kong was once under the jurisdiction of Xin’an County, and the then county seat was located in now Nantou Old Town.

11 “The original pseudo-classic style buildings in Nantou used film-making techniques, where the pillars and eaves were largely made of plastic foam and used paint spray. These buildings are neither reproductions in another location nor rebuilt on the original site.” Source: Daily Sunshine, 2011-04.

12 The Donguan Assembly Hall was built in 1907, and the Ancestral Hall of WEN Tianxiang Duke of Xinguo was built in 1804. Source: Nantou Old Town Museum, Shenzhen Nantou Old Town

History and Cultural Relics, 100–101.

13 “An investment of more than 3.8 million yuan was given to renovate the signboards of 178 shops and paint on the exterior walls of the first floor of the buildings.” Source: Nanfang Daily, 2011-08.

14 Details can be found in the Shenzhen’s 13th Five-Year Plan for Urban Renewal (2016–2020) (SMPRC/2016/824).

15 Source: China Business Journal, 2018-04.

16 Nantou Meeting Room (1 Chaoyang North Street), Zhanjiang Beef Offal Restaurant (72 Zhongnan South Street), Jinji Shop (44 Zhongshan East Street), House No.17, and the temporary sheds.

17 Details can be found in the Master Plan of Integrated Renovation of Urban Villages (Old Villages) in Shenzhen (2019–2025) (SMPNRB/2019/104).

18 The redevelopment of the old town of Hubei was undertaken by China Resources with phase-one construction launched in September 2019. The redevelopment of Baishizhou was undertaken by LVGEM with all rentals terminated in 2019.

19 “Regulate and guide all districts to promote large-scale renovation for renting in urban villages in an orderly manner within the designated renovation areas. The buildings which meet relevant requirements can be included in the public housing security system.” Source: Master Plan of Integrated Renovation of Urban Villages (Old Villages) in Shenzhen (2019–2025) (SMPNR/2019/104).

20 “It is reported that on 5 March, 2020, the district government issued a No. 1 special task order on the conservation and utilization of Nantou Old Town. In just 10 days, the Nantou Sub-district Office completed negotiations with 1,324 people and accomplished the rental sourcing work of 88 buildings, approximately 40,000 m2, within the demonstration section zone.” Source: Nanshan District Government’s No. 1 Task Order Facilitates the Completion of Source Renting of the 88 Buildings in the Demonstration Zone of Zhongshan South Street and Zhongshan North Street, 2020-04-09.

21 Source: China Reform Daily, 2020-10-18.

22 Source: Southern Metropolis Daily, 2020-06-30.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________